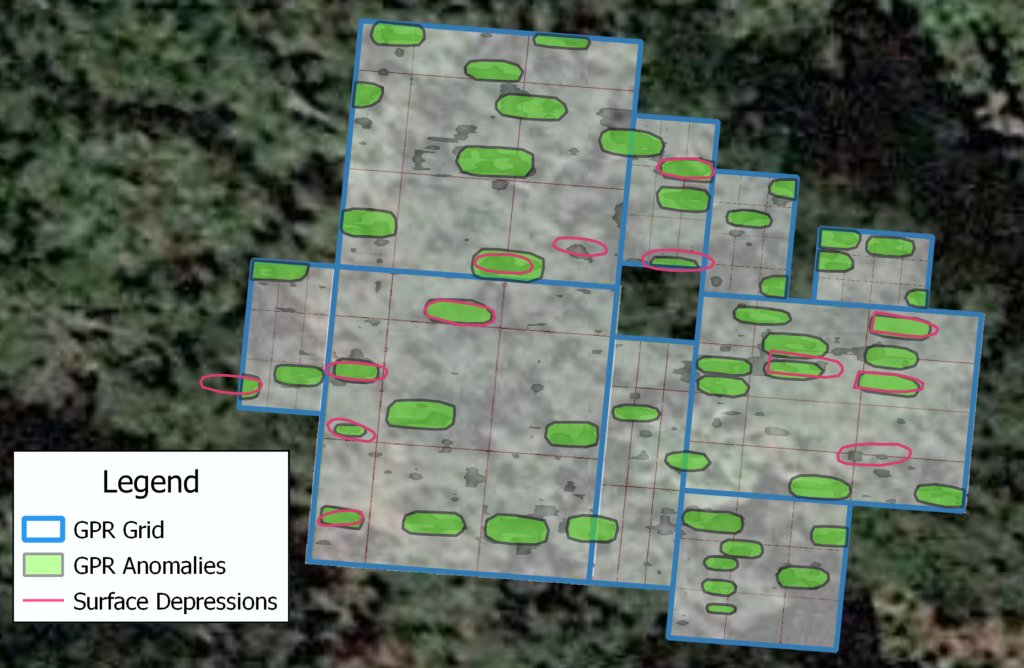

Who is buried in Rosewood’s African American cemetery? To answer this question we must combine archaeological and documentary evidence. Visitors to Rosewood Black burial ground can see several long depressions, clearly representing historic graves. Depending on ground cover and training, most visitors identify between 12 and 15 graves. Most of them are unmarked and visible only because of depressions. An additional 40+ graves were identified by a ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey in 2019. You can explore the results of that work in 3D/VR by visiting the Virtual Rosewood Cemetery here.

Only three gravestones have been recovered at the site. The other graves either had ephemeral markers (e.g., wood) or their markers were removed during the past century. The graves of several infants are likely visible in the lower right-hand corner of the above map. Assigning names to the individual graves lacking markers is difficult, if not impossible. That is not to say we cannot locate the names of persons who are buried at the site. The following table includes a list of those buried at the cemetery as revealed via a thorough examination of historical documents, specifically State of Florida Certificates of Death, oral histories, census records, and newspapers.

| Name | Race | Age | Birthplace | Birth | Death | Data Source |

| Ervinel Barclay | Black | 3 | Rosewood | 1919 | 1922 | Cert. of Death |

| Halton Isiah Benbow | Black | 1 | Rosewood | 1919 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Nancy Bradley | Black | 65 | South Carolina | 1841 | 1906 | Cert. of Death |

| Nancie (Grant) Bradley | Black | 19 | Levy County | 1898 | 1917 | Cert. of Death |

| Virginia (Carrier) Bradley | Black | 42 | Leon County | 1879 | 1921 | Cert. of Death |

| Frank Bunn | Black | 66 | 1852 | 1918 | Cert. of Death | |

| Haywood/Hayward Carrier | Black | 1867 | ??? | Census, Oral History, Newspapers | ||

| Sylvestor Carrier | Black | 31 | Florida | 1891 | 1923 | Census, Oral History, Newspapers |

| James Carrier | Black | 56 | Florida | 1866 | 1923 | Census, Oral History, Newspapers |

| Sarah Carrier | Black | 50 | Gainesville | 1873 | 1923 | Census, Oral History, Newspapers |

| Sam Carter | Black | 49 | South Carolina | 1874 | 1923 | Census, Oral History, Newspapers |

| Edmond “Ed” Goins | Black | 70 | North Carolina | 1850 | 1920 | Cert. of Death |

| Harry Goins | Black | 1 | Rosewood | 1915 | 1917 | Cert. of Death |

| Martine Goins | Black | 53 | North Carolina | 1852 | 1905 | Cert. of Death, Gravestone |

| Orlando Gordon | Black | 21 | North Carolina | 1896 | 1917 | Cert. of Death |

| Lexie Gordon | Black | 55 | North Carolina | 1867 | 1923 | Census, Oral History, Newspapers |

| Infant Griffin | Black | 0 | Rosewood | 1919 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Simon Griffin | Black | 61 | Florida | 1859 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Charles Bacchus “CB” Hall | Black | 73 | South Carolina | 1847 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant Hall | Black | 0 | Rosewood | 1919 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant Holloman | Black | 0 | Sumner | 1920 | 1920 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant Ingram | White | 0 | Sumner | 1918 | 1920 | Cert. of Death |

| Lettie (Hall) Jones | Black | 43 | Florida | 1875 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Jones Parker | Black | 23 | Florida | 1895 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Agnora King | Black | 66 | Florida | 1852 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant King | Black | 1 | Inverness, FL | 1919 | 1920 | Cert. of Death |

| Queenie Z. (Goins) King | Black | 20 | Florida | 1879 | 1900 | Gravestone |

| Agnes E. (Goins) Marshall | Black | 34 | North Carolina | 1883 | 1917 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant McQueen | Black | 0 | Sumner | 1919 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant McQueen | Black | 0 | Sumner | 1918 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant McQueen | Black | 0 | Florida | 1920 | 1920 | Cert. of Death |

| Cary Lee Monroe | Black | 0 | Florida | 1917 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Clara Monroe | Black | 14 | Rosewood | 1903 | 1917 | Cert. of Death |

| Sophia Monroe | Black | 34 | North Carolina | 1894 | 1917 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant Nelson | Black | 0 | Florida | 1919 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Ella Reed | Black | 39 | Rosewood | 1883 | 1922 | Cert. of Death |

| George Robinson | Black | 38 | Florida | 1880 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant Robinson | Black | 0 | Florida | 1920 | 1920 | Cert. of Death |

| Janetta (Carter) Robinson | Black | 41 | South Carolina | 1878 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Mrs. S. M. (Sallie) Sauls | White | 62 | Georgia | 1857 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| Infant Swayne | Black | 0 | Florida | 1919 | 1919 | Cert. of Death |

| E. P. Walden | Black | 63 | 1842 | 1905 | Gravestone | |

| Amos Williams | Black | 20 | Florida | 1899 | 1918 | Cert. of Death |

| Fannie Williams | Black | 26 | Florida | 1874 | 1907 | Cert. of Death |

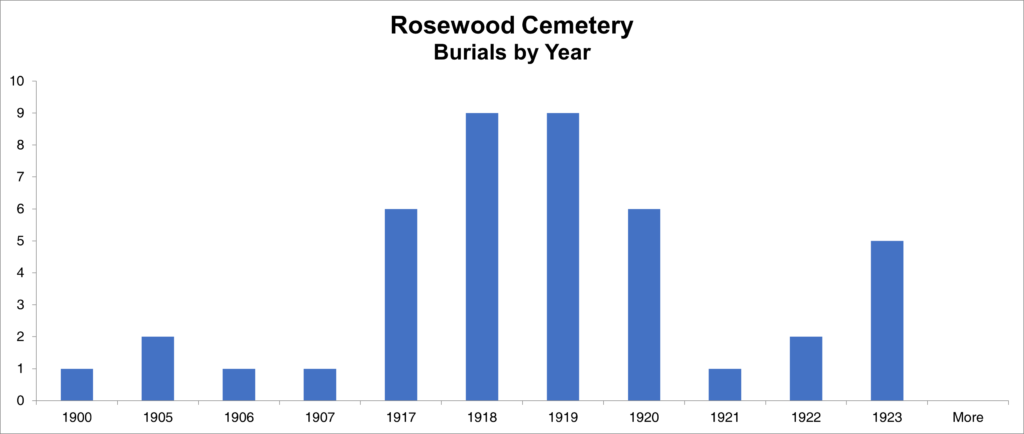

This spreadsheet includes additional details not listed in the table above. It is unlikely the above table includes all burials at the cemetery, although it is much closer to the 50-60+ graves revealed by mapping and GPR survey work. Charting out the number of burials by year provides additional information.

A number of patterns are visible in this data, but they may be misleading. For instance, the absence of burials before 1900 and the large number of infant deaths between 1917 and 1920. It is likely that burials took place prior to 1900, but were simply not reported. This is possible as the state of Florida did not require death certificates be recorded until 1917.

The large number of infant deaths between 1917 and 1920 may be explained in a couple of different ways. First, the uptick in 1918 and 1919 may coincide with the 1918 influenza pandemic. Although, it is just as possible that we have access to these records because Florida required all deaths be recorded beginning in 1917. If this is the case, then the high infant mortality rates in the past means other children are likely buried in the cemetery. In truth, America continues to struggle with the the fact that infant mortality was far more common than we tend to acknowledge today.

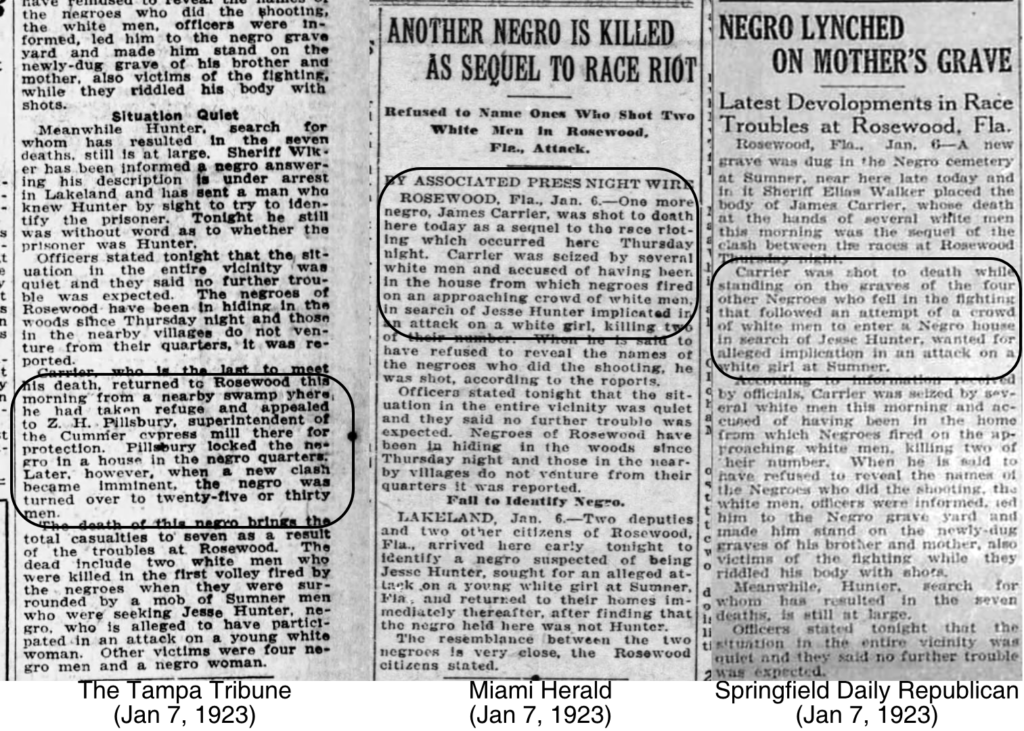

The fact that burials continue through 1922 suggests the victims of the 1923 race riot are also buried here. Oral history accounts describe, for instance, how James Carrier was caught by a White mob while burying his mother (Sarah) and brother (Sylvester). Newspapers from the first week of 1923 also describe this, an important correspondence between oral history and historical documents.

Several newspapers also ran an image, reportedly showing a group of Whites in Rosewood (or Sumner, the two were commonly mixed up in these reports) standing behind a line of 3 graves reported to be African American burials. It is unlikely that local Whites would have buried Black victims of racial violence and/or taken the bodies 2-3 miles from Rosewood to bury at Shiloh Cemetery in the neighboring community of Sumner. Rural historical cemeteries were mostly segregated along lines of race at this time, and this is certainly the case for cemeteries in Rosewood and Sumner.

Although sometimes credited as being taken in Sumner, the above image was likely taken in Rosewood, and potentially following the burial of James Carrier after his murder at the hands of a White mob. Other aspects of the image caption are incorrect as well. This is not surprising given the fragmented nature of reporting on these events in the past. For instance, there is little evidence that the burned structure is the remains of “shanties” but rather one of the large houses inhabited by one of Rosewood’s Black families. Furthermore, there is little evidence that African Americans were heavily armed at the Carrier home, although we know several families took shelter there during the first week of 1923 and were able to initially protect themselves.

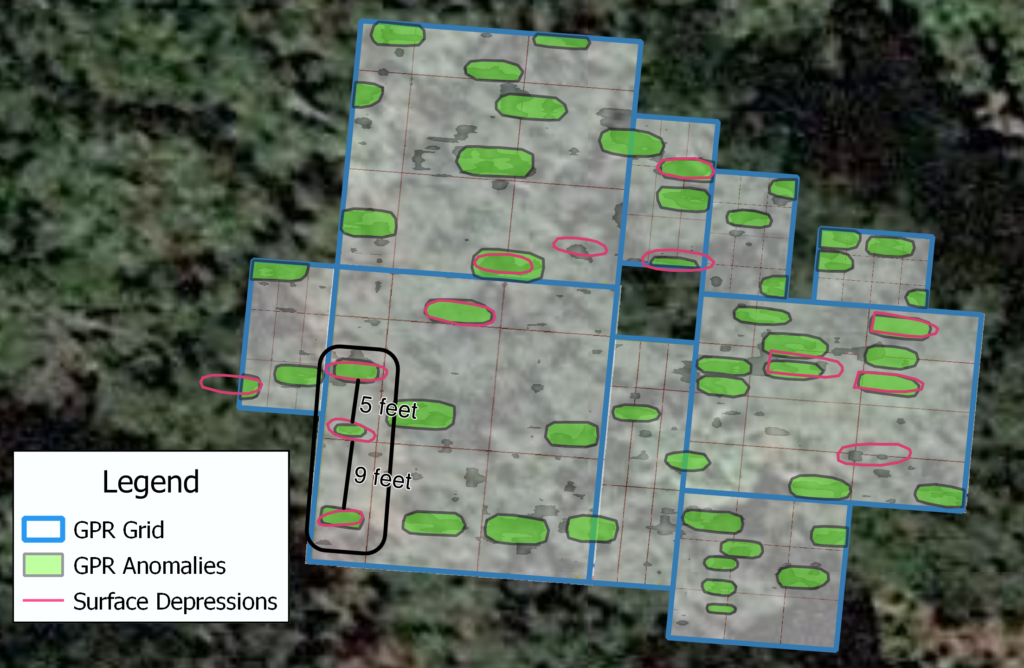

Although the graves are mounded in the above photo, without constant re-mounding and other maintenance, such burials in Florida’s sandy soil tend to ‘sink’ and form depressions. This is partly due to decomposition of the burials, and partly due to the nature of soil weathering in Florida. While extracting exact measurements from the image above is difficult, the positioning and distances between these three graves appear to match a line of graves along the western edge of Rosewood’s cemetery. The spacing is similar and their placement next to a road suggests it may be the same place.

Researchers have to combine archaeology and the fragmentary documentary record to craft a more complete interpretation of Rosewood’s African American cemetery. This includes accurately locating – and possibly correcting – erroneous or otherwise unreliable data. In the case of Rosewood archaeology, census records, death certificates, historical newspapers, and oral histories all combine to remind us of the importance even a small patch of ground in Levy County might have regarding larger patterns of violence in American history. In relation to locating the historical newspaper image, it may be of another location or even be of burials associated with the White men who died in 1923. Until firm proof is forthcoming – perhaps original documentation from the photographer – there is room to theorize.